This video connects some gods of ancient Egypt and India, so I think it’s worth discussing these motifs.

CONTENTS: FIND IN PAGE

MYTHS OF COMETS, DRAGONS, SERPENTS

EARLIEST VENUS DRAGON/SERPENT MYTHS

PREHISTORIC COMETS AS SERPENTS OR DRAGONS

EARLY ROCK ART OF COMETS ETC AS SERPENTS OR DRAGONS

ANCIENT SERPENT OF EGYPT & INDIA

ENGLISH WORD, SNAKE

The word snake in English originates from Old English snaca, which itself derives from Proto-Germanic snak-an (e.g., German Schnake meaning 'ring snake' and Swedish snok meaning 'grass snake'). It traces further back to the Proto-Indo-European root (s)nēg-o, meaning "to crawl or creep," which also connects to Sanskrit nāgá ('snake') and the English word sneak1,2. The term gradually replaced the Old English word næddre, which narrowed in meaning to refer specifically to the adder, a venomous snake1.

In other languages, similar spellings and etymological roots for "snake" include:

German: Schlange, derived from ancient Germanic languages6.

Latin: anguis, meaning snake or serpent, and related to the Latin word serpens ('creeping')4,6.

Russian: змея (zmeya), stemming from Slavic roots5.

French: serpent, from Latin serpens6.

Many Indo-European languages share nasal sounds (e.g., "n" or "m") and creeping-related consonants (e.g., "k," "g," "s") in their words for snake. For example, Sanskrit uses nāgá, Lithuanian has angis, and Albanian features ngjalë ('eel'), reflecting shared linguistic patterns across cultures4.

Now starting with NAGA: https://thetalklist.com/snake-in-different-languages/

Ancient Egyptian: nehebkau -- Ancient Hindu: naga -- Maori: nakahi -- Tuvaluan: nakele -- Bambara: nakon -- Tswana: nogana -- Sepedi: noga -- Luo: ng’adi -- Tongan: ngaue -- NKo: (ngenden) -- Thai: (ngu) -- Lao: (ngu) -- Latin: anguis -- English: snake -- Icelandic: snákur -- Jamaican Patois: sneek -- Krio: sneik -- Papiamento: sneku -- Tok Pisin: snek -- Yiddish: (shnek) -- Marshallese: kunu -- Sesotho: noha -- Hebrew: (nahash) -- Hawaiian: nahesa -- Kiga: nyoka -- Kikongo: nyoka -- Kituba: nyoka -- Lingala: nyoka -- Shona: nyoka -- Swahili: nyoka -- Tsonga: nyoka -- Nuer: nyok -- Chichewa: njoka -- Bemba: insoka -- Ndau: inyoka -- Ndebele (South): inyoka -- Xhosa: inyoka -- Zulu: inyoka -- Kinyarwanda: inzoka -- Rundi: inzoka -- Chamorro: månnok -- Afar: qaxan -- Hmong: nab -- Breton: naer -- Irish: nathair -- Scots Gaelic: nathair -- Welsh: neidr

Luxembourgish: Schlaang -- German: Schlange -- Hunsrik: schlange -- Danish: slange -- Norwegian: slange -- Walser: slangg -- Afrikaans: slang -- Dutch: slang -- Frisian: slang -- Limburgish: slang -- Volapük: slawüka -- Kazakh: (zhylan) -- Kyrgyz: (zhylan) -- Bashkir: (ylan) -- Tatar: (ylan) -- Zazaki: yilan -- Uyghur: (yilan) -- Crimean Tatar: yılan -- Turkish: yılan -- Meadow Mari: (ulan) -- Azerbaijani: ilan -- Turkmen: ilan -- Uzbek: ilon -- Batak Karo: ular -- Batak Simalungun: ular -- Batak Toba: ular -- Betawi: ular -- Iban: ular -- Indonesian: ular -- Makassar: ular -- Malay: ular -- Minang: ular -- Balinese: ula -- Acehnese: ulee -- Javanese: ulo -- Madurese: ulo -- Ilocano: urat -- Chuvash: (yҫyl) -- Hungarian: kígyó -- Basque: suge -- Ossetian: саг (sag) -- Ewe: tsitsinya -- Khasi: u nyit -- Russian: (zmeya) -- Macedonian: (zmija) -- Serbian: (zmija) -- Bulgarian: (zmiya) -- Ukrainian: (zmiya) -- Belarusian: (zmya) -- Bosnian: zmija -- Croatian: zmija -- Silesian: żmija -- Upper Sorbian: zmiju

Romani: şarpa -- Romanian: șarpe -- Mauritian Creole: serpan -- Seychellois Creole: serpan -- Italian: serpente -- Ligurian: serpente -- Lombard: serpente -- Esperanto: serpento -- Baoulé: serpent -- Dombe: serpent -- French: serpent -- Occitan: serpent -- Corsican: serpe -- Galician: serpe -- Spanish: serpiente -- Walloon: serpint -- Sicilian: serpi -- Catalan: serp -- Friulian: serp -- Maltese: serp -- Nepalbhasa (Newari): (sarp) -- Nepali: (sarp) -- Sanskrit: (sarpaḥ) -- Sinhala: (sarpaya) -- Sami (North): sarvvis -- Tibetan: sbrul -- Dyula: seere -- Punjabi (Shahmukhi): (sanp) -- Sindhi: (sanp) -- Urdu: (sanp) -- Awadhi: (sanp) -- Bhojpuri: (sanp) -- Hindi: (sanp) -- Maithili: (sanp) -- Marwadi: (sanp) -- Konkani: (sap) -- Marathi: (sāp) -- Assamese: (sap) -- Bengali: (sap) -- Meiteilon (Manipuri): (sap) -- Dogri: (sapp) -- Punjabi (Gurmukhi): (sapp) -- Gujarati: (sāp) -- Odia (Oriya): (sap) -- Pangasinan: sawa -- Jingpo: (asi) -- Fon: sã -- Hakha Chin: (sâ) -- Cantonese: (se) -- Chinese (Simplified): (shé) -- Chinese (Traditional): (shé) -- Avar: (ch’al) -- Chechen: (ch’ila) -- Mingrelian: (chia) -- Mam: chik -- Qʼeqchiʼ: chilal -- Nahuatl (Eastern Huasteca): cōātl -- Portuguese (Brazil): cobra -- Portuguese (Portugal): cobra -- Vietnamese: con rắn -- Latgalian: čūska -- Latvian: čūska -- Yoruba: ejò -- Fijian: gata -- Samoan: gata -- Albanian: gjarpër -- Lithuanian: gyvatė -- Georgian: (gveli) -- Igbo: agwọ -- Finnish: käärme -- Slovenian: kača -- Aymara: katari -- Dinka: kor -- Haitian Creole: koulèv

MYTHS OF COMETS, DRAGONS, SERPENTS

Snake: This refers to the real-life, legless reptiles that slither across the ground—like pythons, cobras, or garter snakes. It's rooted in biological and scientific contexts.

Serpent: While it can also mean a snake, "serpent" often carries a more symbolic or poetic weight. It’s a word rich in mythology, religion, and literature. Serpents are often depicted as mysterious, cunning, or even sacred creatures—like the serpent in the Bible or in ancient Egyptian and Greek stories.

Ancient myths frequently link comets, dragons, and serpents through shared symbolism of destruction, renewal, and celestial phenomena.

Comets as Dragons and Serpents

Comets, with their long, fiery tails, were often interpreted as cosmic serpents or dragons. Many cultures described them as "fiery snakes" in the sky, bringing omens of catastrophe or divine intervention1,6.

In Norse mythology, the Midgard Serpent (Jörmungandr) thrashing in the sea mirrors descriptions of comet-induced tsunamis.

Chinese legends depict dragons as celestial beings linked to comets, particularly those that appeared before disasters (e.g., Halley’s Comet in 530 CE, which was blamed for dynastic collapse)3.

Dragons and Serpents as Cosmic Forces

The ouroboros (a serpent eating its tail) symbolizes cyclical destruction and rebirth, akin to comets' periodic returns7.

Mesopotamian myths like Tiamat and Leviathan describe serpentine chaos monsters, possibly inspired by comet impacts causing floods or climate shifts (e.g., the Younger Dryas event ~12,900 years ago)5.

Greek myths conflate dragons (drakōn) with comets; Apollo’s slaying of Python may allegorize a comet’s disruption of Delphi’s oracle4.

Cultural Parallels

Europe: Anglo-Saxon chronicles record "dragons" flying before invasions, likely referencing cometary apparitions6.

Ireland: The hero Cú Chulainn’s death was tied to a comet, with his spear described as a "dragon’s flame"3.

Russia: Folklore depicts dragons as meteors with "golden wings," blending serpentine and celestial traits8.

Conclusion: The triad of comets, dragons, and serpents reflects humanity’s attempt to explain celestial events through myth, merging awe for cosmic fire with primal fear of serpents as agents of chaos and renewal.

MYTHS OF SERPENTS & BIRDS

1. Comets as Fiery Serpents or Dragons

Many cultures described comets as "sky serpents" due to their long, glowing tails. Greek and Roman sources, including Hesiod, depict comets as multi-headed dragons breathing fire, matching telescopic observations of fragmenting comets3.

The Aztec god Quetzalcoatl ("feathered serpent") may symbolize a comet’s appearance, blending serpentine and avian traits1.

Norse mythology’s Midgard Serpent (Jörmungandr) thrashing in the sea mirrors descriptions of cometary impacts causing tsunamis, aligning with the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis (~12,900 years ago)2.

2. Dragons as Cosmic and Earthly Forces

Greek mythology classifies dragons into four types:

Dracones: Giant serpents guarding treasures (e.g., the Colchian Dragon protecting the Golden Fleece)5.

Cetea: Sea serpents like those in Phoenician and Hebrew myths (Leviathan, Yam).

Chimaera: Fire-breathing hybrids (lion-goat-serpent), possibly inspired by cometary fragmentation5.

Dracaenae: Serpent-women like Echidna, linking reptilian and human traits5.

Chinese and Welsh myths describe dragons as celestial omens, with the Welsh Red Dragon symbolizing sovereignty and conflict7.

3. Connection to Birds

Feathered serpents (Quetzalcoatl, Asian dragons) blend serpentine and avian features, possibly representing comets with trailing debris resembling wings1,8.

In Greek myth, the dragon Ladon (guardian of the Golden Apples) and Typhon (a storm giant with serpent limbs) were sometimes depicted with avian traits, reinforcing their cosmic ties5.

Norse legends describe eagles and dragons in conflict (e.g., the eagle Hræsvelgr and serpent Níðhöggr), mirroring celestial battles between comets and stars2.

Conclusion

The triad of comets, dragons, and serpents reflects ancient attempts to explain celestial disasters through myth. Comets, with their serpentine tails and fiery impacts, became dragons in folklore—symbolizing both destruction (floods, plagues) and renewal (cyclical time, divine intervention). Meanwhile, birds in these myths often serve as intermediaries between earth and sky, further blending serpentine and avian imagery in cosmic narratives.

VENUS COMET, DRAGON, SERPENT

Several cultures mythologized Venus as a serpent, dragon, or comet due to its erratic movements, brightness, and occasional comet-like appearance in antiquity.

1. Mesopotamian & Near Eastern Traditions

Inanna/Ishtar (Sumer/Akkad)

Venus was linked to the goddess Inanna (Sumer) and Ishtar (Akkad/Babylon), who was described as a "celestial dragon" or "whirling serpent" in hymns, with epithets like "great blazing serpent who writhes in the sky." Texts compare her to a comet with a "tornado-like tail" and associate her with storms and war6.

The Epic of Gilgamesh describes Ishtar’s wrath as akin to a celestial disaster, possibly reflecting ancient observations of Venus’s atmospheric phenomena.

2. Greek & Roman Myths

Eurynome and Ophion (Neolithic Greece)

The primordial goddess Eurynome ("wide-wandering one," possibly Venus) transformed the North Wind into the serpent Ophion, who coiled around her and hatched the Cosmic Egg—linking Venus to serpentine creation myths1.

Aphrodite/Venus

Though primarily a love goddess, her birth from sea foam (after Uranus’s castration) mirrors cometary imagery. Some scholars suggest her myth preserves fragmented memories of Venus appearing as a bright, disruptive "comet"3.

3. Mesoamerican Feathered Serpents

Quetzalcoatl & Kukulkan (Aztec/Maya)

The feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl was explicitly tied to Venus, called Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli ("Dawn Lord") in its morning-star phase. The Maya named it Chak Ek’ ("Red Star"), associating it with war and serpentine omens5,7.

The Dresden Codex depicts Venus as a fire-breathing serpent during its heliacal risings, marking times of conflict7.

4. Egyptian & Cometary Venus

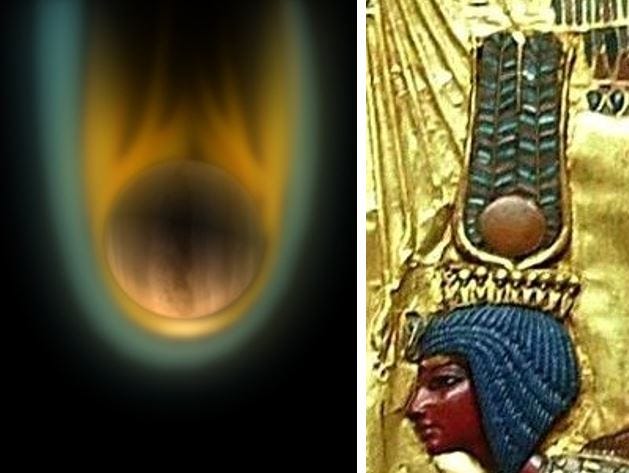

Cleopatra as Venus-Comet

Some fringe theories (e.g., the God King Scenario) propose that Egyptian queens like Cleopatra were symbolically linked to Venus in comet form, wearing crowns resembling cometary plumes4.

Hathor (a sky goddess) was occasionally depicted with serpentine or celestial traits, possibly influenced by Venus’s behavior4.

5. Norse & Celtic Parallels

Norse "Dragon Stars"

While not explicitly Venus, Níðhöggr (a serpent gnawing the World Tree) and Fafnir (a dragon) may reflect comet/planet myths.

Celtic "Nathair" (Serpent)

Venus’s dual morning/evening star phases could align with serpentine duality in Celtic lore.

Conclusion: Venus’s serpent/comet symbolism arises from its bright, erratic visibility, often interpreted as a celestial dragon or omen of upheaval. Cultures from Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica tied it to war, creation, and chaos, blending astronomical observations with mythic archetypes.

EARLIEST DRAGON MYTHS

The earliest dragon myths emerged independently across multiple ancient civilizations, with some of the oldest recorded examples dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE or earlier. Here are the key early dragon myths:

Mesopotamia (c. 2100 BCE)

The Mušḫuššu, a serpentine dragon with lion-like forelegs and eagle-like hind legs, appears in Mesopotamian art and texts as a symbol of chaos1,4.

The Enuma Elish (late 2nd millennium BCE) describes Tiamat, a primordial dragon goddess who transforms into a horned serpent1,8.

The Sumerian myth of Kur, a dragon who abducted the goddess Ereshkigal, is among the earliest recorded5.

Egypt (pre-2700 BCE)

Apep (or Apophis), the serpentine embodiment of chaos, appears in Egyptian creation myths as a foe of the sun god Ra1,8.

Indo-European Proto-Mythology (6000–4500 BCE)

The storm god vs. chaos serpent motif (e.g., Zeus vs. Typhon, Indra vs. Vṛtra) likely originated in Proto-Indo-European culture2.

Vṛtra from the Rigveda (c. 1500 BCE) is a multi-headed serpent blocking cosmic waters1.

China (6200–5400 BCE)

Dragon-like zoomorphic depictions appear in Xinglongwa and Hongshan cultures, evolving into the benevolent Chinese dragon associated with water and imperial authority3,2.

These early myths typically portrayed dragons as serpentine forces of chaos or divine power, with regional variations emerging later (e.g., fire-breathing in Greek/Roman traditions)1,2. The universality of dragon myths suggests either a shared ancestral tradition or convergent symbolic evolution across cultures.

EARLIEST SERPENT MYTHS

The earliest serpent myths date back tens of thousands of years, with evidence of serpent worship appearing in some of humanity's oldest symbolic artifacts. Here are the key early serpent myths:

Prehistoric Origins (70,000+ Years Ago)

The oldest known serpent worship comes from Botswana's Tsodilo Hills, where a 70,000-year-old serpent head was carved into rock, suggesting early ritual significance8.

Ancient Mesopotamia (3rd Millennium BCE)

Ningizzida, a Sumerian serpent god with human features, guarded heaven's gates alongside Dumuzi and was associated with healing and fertility1,3.

Tiamat, the primordial dragon-serpent of chaos in the Enuma Elish, represented the earliest cosmic serpent archetype1.

Early Egypt (Pre-Dynastic Period)

Wadjet, the cobra goddess of Lower Egypt, was worshipped as early as 3000 BCE and symbolized royal protection via the Uraeus headdress2,6.

Apep, the eternal chaos serpent opposing Ra, embodied destruction in solar mythology1,7.

Minoan Crete (2000-1450 BCE)

The Snake Goddess figurines held serpents as symbols of wisdom and divine power, blending chthonic and celestial aspects1,3.

Proto-Indo-European Motifs

The storm god vs. serpent conflict (e.g., Zeus vs. Typhon, Indra vs. Vṛtra) likely originated in Neolithic mythology1,3.

The ouroboros, depicting cyclical renewal, first appeared in Tutankhamun's tomb but may have earlier roots2,7.

These myths reflect serpents' dual symbolism—representing both chaos/evil (Apep, Tiamat) and renewal/healing (Ningizzida, ouroboros)—while their prevalence suggests deep psychological roots tied to primate evolutionary fears1,4.

EARLIEST VENUS DRAGON/SERPENT MYTHS

The earliest myths linking Venus to serpent or dragon symbolism appear in prehistoric Eurasian and Mesoamerican cultures, where the planet's cyclical movements were often associated with cosmic serpents. Key examples include:

1. Eurasian Gravettian Culture (24,000 BCE)

The Mal'ta-Buret culture of Siberia created serpent carvings alongside "Venus figurines," suggesting an early astro-mythological connection between fertility goddesses and serpentine symbols. This culture, ancestral to Native Americans and Europeans, may represent the first known Venus-dragon association.1

2. Proto-Indo-European Storm Myths (6000-4000 BCE)

The conflict between storm gods (later associated with Jupiter/Zeus) and serpentine chaos beings (like Vṛtra or Typhon) incorporated Venus symbolism. Venus' dual appearance as Morning/Evening Star mirrored the serpent's chthonic-celestial duality.3,6

3. Mesoamerican Feathered Serpents (1400 BCE onward)

Quetzalcoatl and Kukulkan explicitly merged Venus' orbital cycle (584-day synodic period) with serpent mythology. Their myths describe the planet as a celestial serpent shedding its skin (phases) while moving between underworld and sky realms.

4. Chinese Azure Dragon (5000 BCE)

The celestial dragon representing Jupiter's path also incorporated Venus symbolism, particularly in its associations with jade (linked to Venus' brightness) and watery domains.1

These traditions share core motifs: serpents/dragons as mediators between Venus' celestial phases and earthly cycles of fertility/destruction, often visualized through plasma discharge patterns in ancient petroglyphs.5,7 The Venus-serpent link appears earliest in Siberian and European Upper Paleolithic artifacts before radiating globally via later cultural diffusion.

PREHISTORIC COMETS AS SERPENTS OR DRAGONS

Prehistoric myths worldwide commonly linked comets to serpent or dragon imagery, often as catastrophic omens. Key examples include:

1. Younger Dryas Impact (12,900 years ago)

The Hiawatha Crater impact (Greenland, ~12,000 BCE) may have inspired global dragon myths, as comets fragmenting in Earth’s atmosphere could resemble fiery serpents. Indigenous tales like the Miami’s “horned serpent” or Shawnee’s “sky panther” describe comet impacts as serpentine forces3.

2. Proto-Indo-European Storm Myths

Vedic Vṛtra (a multi-headed serpent) and Greek Typhon (a dragon “breathing forth burning fire”) mirror comet descriptions, with telescopic observations showing comet heads resembling serpents or animal forms2.

3. Slavic Fiery Serpents (1092 CE)

East Slavic chronicles depict three-headed “fiery serpents” emerging from darkened skies, likely describing bolides or comet fragments4. These were linked to fallen angels or devils in folklore.

4. Aboriginal Australian Traditions

The Rainbow Serpent may derive from Halley’s Comet transits, while Arrernte clans viewed comets as ancestral spears or death omens5. The Tanganekald tied comets to sickness and drought.

5. Mesoamerican Feathered Serpents (539 CE Impact)

The Itza Maya sculpted earthen shrines to a “Celestial Serpent” after a comet strike in the southeastern U.S., aligning with myths of a sky panther or falling sun3.

These myths universally portray comets as serpentine destroyers, blending plasma discharge patterns (like comet tails) with chthonic symbolism. The consistency across cultures suggests shared ancestral memories of cosmic catastrophes6,7.

EARLY ROCK ART OF COMETS ETC AS SERPENTS OR DRAGONS

Several prehistoric rock art sites before 2000 BCE depict comets or celestial phenomena as serpents or dragons, reflecting ancient sky-watchers' interpretations of cosmic events. Key examples include:

1. Scandinavian & Alpine Rock Art (Bronze Age, ~1800–500 BCE)

Coiling serpents and plasma-like patterns in petroglyphs resemble comet tails or auroral discharges, possibly recording intense solar storms or cometary apparitions. These motifs align with Indo-European storm-serpent myths (e.g., Typhon, Vṛtra)1,5.

2. North American Comet Petroglyphs (Prehistoric)

Chaco Canyon (New Mexico): A spiral petroglyph with serpentine extensions may depict a comet’s plasma discharge, mirroring laboratory plasma experiments5.

Sego Canyon (Utah): Barrier Canyon-style rock art includes anthropomorphic figures with serpentine appendages, interpreted as celestial beings linked to comets or meteors6.

3. African Rain Snake Panel (Lesotho, 70,000+ BCE)

A giant serpent painted alongside celestial symbols may represent a comet or plasma event, tied to later myths of sky serpents bringing rain or destruction1,5.

4. European Megalithic Art (Neolithic, 4000–2000 BCE)

Irish passage tombs (e.g., Newgrange): Carvings of sinuous lines and spirals may encode cometary trajectories, later mythologized as Celtic serpent deities1.

Iberian rock art: Abstract serpentine motifs in Galicia align with solstices, suggesting sky-serpent symbolism tied to cosmic cycles1.

Shared Themes

Plasma Discharge Patterns: Physicist Anthony Peratt identified petroglyph designs matching high-energy plasma formations, including twisted serpents resembling comet tails5.

Mythological Links: Global serpent-dragon myths (e.g., Apep, Quetzalcoatl) likely originated from prehistoric observations of cometary plasma displays5,7.

ANCIENT SERPENT OF EGYPT & INDIA

youtube.com/watch?v=xXZOSSLICiA&t=8s

This figure is on the wall of Seti I’s tomb in Egypt, 5-headed snake around the king.

Compare this, which shows the god-king in India guarded by a 5-headed snake. The author added the red color for highlighting.

The transcript explores the potential connection between Nagas, reptilian beings from ancient Indian texts, and the recently discovered vast underground city beneath the Khafre pyramid in Egypt. It questions whether the similarities between Naga depictions in India and those of Nehebkau in Egypt are coincidental, considering both iconography and linguistic resemblances.

The Tomb of Seti I in Egypt features a five-headed snake guarding a figure, mirroring similar imagery in ancient India. The Egyptian Book of Gates also depicts a person lying on a snake, with detailed spots and stripes that are consistent with Indian depictions of deities reclining on snakes.

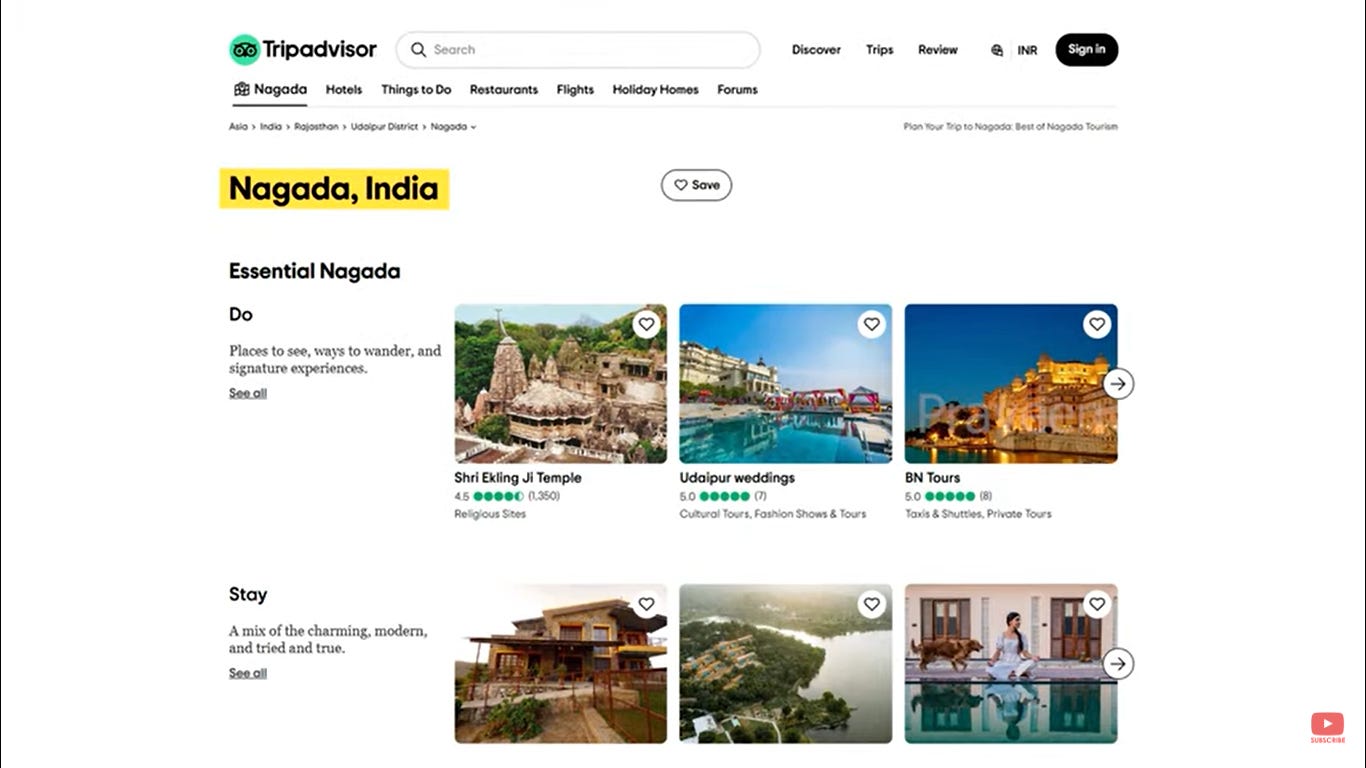

Linguistically, the Egyptian deity Nehebkau shares a similar pronunciation with Naga, strengthening the argument for a shared identity. The cult of Nehebkau originated in the ancient Egyptian city of Naqada, where numerous serpent-related artifacts have been discovered.

Intriguingly, there is an ancient city called Nagada in Rajasthan, India, where locals recount stories of its founding by a reptile king named Nagaditya. They believe in a vast underground realm called Nagaloka, ruled by Nagas, which mirrors the underground tunnels and chambers found beneath the Pyramid of Khafre.

Ancient Egyptian texts describe Nehebkau as the guardian and ruler of the underworld, aligning with the Indian belief in Nagaloka, a parallel underground world. This connection is further supported by the discovery of serpent carvings guarding doorways to forbidden treasures in both Egypt and India, suggesting a shared symbolism.

In 1903, the tomb of Prince Amenherkhepshef in Egypt was found to have two serpents carved on the doorway, guarding a chamber that had been looted. Similarly, in 2011, a vault in the Padmanabhaswamy temple in India was found to have doors protected by two Nagas, signifying a forbidden treasure.

The transcript proposes that the Egyptian authorities may be hesitant to grant access to the underground areas due to the potential for immense wealth and advanced scientific information. It raises the possibility that these underground areas are connected to Atlantis and questions whether reptile-like beings still inhabit the underground in Egypt.

Ultimately, the transcript encourages viewers to consider the evidence and contemplate whether the similarities between Naga and Nehebkau, the cities of Naqada and Nagada, and the serpent-guarded treasures are mere coincidences or evidence of a deeper connection between ancient Indian and Egyptian cultures.

MANY FACES OF VENUS

"The Many Faces of Venus" by Ev Cochrane explores how ancient cultures perceived Venus, not as the serene planet we know today, but as a dynamic and often fearsome celestial body. Cochrane challenges conventional uniformitarian views of astronomy by proposing that Venus underwent dramatic changes in the inner solar system within human memory.

The book delves into a wealth of cross-cultural myths and iconography, suggesting that Venus was once a much more prominent and erratic presence in the sky. Ancient accounts depict Venus as a blazing comet-like object, a "terrible star," or a sky god engaged in cosmic battles.

Cochrane analyzes the myths of various cultures, including the Greeks, Egyptians, Babylonians, and Mesoamericans, to demonstrate a common thread of catastrophic events associated with Venus. These events include floods, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions, which may reflect actual celestial phenomena.

The author also explores the connection between Venus and other celestial bodies, such as Mars and Saturn, in ancient mythology. He argues that these planets were once part of a complex celestial configuration that dramatically influenced Earth's environment and human history.

"The Many Faces of Venus" challenges readers to reconsider their understanding of ancient mythology and astronomy, suggesting that these stories may contain valuable insights into the dynamic history of our solar system. Cochrane's work contributes to the Electric Universe theory, which posits that electromagnetic forces play a crucial role in shaping celestial phenomena.

The book further suggests that the cataclysmic events associated with Venus may have had a profound impact on human consciousness and the development of civilization. Ancient cultures may have developed elaborate rituals and mythologies to cope with the trauma of these events.

Cochrane emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary research, combining insights from mythology, astronomy, geology, and plasma physics, to reconstruct the true history of our solar system. He encourages readers to question established paradigms and explore alternative explanations for the mysteries of the past.

Ultimately, "The Many Faces of Venus" presents a provocative and thought-provoking challenge to conventional views of astronomy and mythology, suggesting that the ancient sky was a much more dynamic and turbulent place than previously imagined. It proposes that Venus played a central role in shaping Earth's history and human civilization.

THE VENUS COMET

Ev Cochrane's The Many Faces of Venus argues that ancient myths and artwork depict Venus as a comet-like celestial body, fundamentally different from its current appearance. Key points include:

Catastrophic Imagery: Ancient descriptions of Venus (e.g., Inanna in Sumerian texts) depict it as a destructive force, with vivid plasma-like features such as "horns" or "tails," inconsistent with its modern benign appearance1,2.

Global Parallels: Similar comet-Venus motifs appear across cultures, suggesting shared observations of celestial phenomena rather than poetic metaphor1,8.

Egyptian Comet Crowns: New Kingdom Egyptian art shows queens wearing crowns mimicking Venus’ cometary form, with "horns" representing bow shocks and twin plumes mirroring its magnetotail. Nefertiti’s crown, for example, features cobras at the points of solar wind impact, aligning with plasma discharge patterns2,8.

Connection to Peratt’s Plasma Findings

Anthony Peratt’s research on ancient petroglyphs identifies global rock art patterns matching high-energy plasma discharges. These include:

"Squatter Man" Figures: Stick figures with flanking dots, corresponding to toroidal plasma instabilities3,4,7.

Venus Comet Motifs: The same plasma configurations (e.g., bifurcated tails, bow shocks) appear in both Peratt’s lab experiments and Venus’ ancient depictions, suggesting observers recorded actual plasma events in the sky2,3,7.

Synthesis

Cochrane and Peratt converge on the idea that ancient witnesses saw Venus and other planets enmeshed in plasma discharges, later memorialized in art and myth. While Cochrane focuses on Venus’ cometary role in myth, Peratt provides the plasma-physics framework to explain the underlying phenomena1,3,7.

VENUS, MARS & SATURN

The Many Faces of Venus argues that ancient mythologies and rock art record catastrophic celestial interactions between Venus, Mars, and Saturn, interpreted through the lens of plasma discharge phenomena. Key points include:

Venus and Mars: The Cometary Crown

Martian "Scarring": Ancient myths describe Mars as a wounded warrior (e.g., the Egyptian Horus-Seth conflict), possibly reflecting plasma discharges between Venus and Mars. Cochrane links this to Peratt’s petroglyphs, which show "Squatter Man" figures—interpreted as high-energy plasma instabilities during close planetary encounters3,5.

Venus as a Comet: Venus was depicted with a "crown" or serpent-like appendages, suggesting a comet-like plasma tail. Egyptian art (e.g., Nefertiti’s crown) mirrors these configurations, theorized to result from Venus’ magnetotail interacting with Mars’ atmosphere during alignments3,7.

Saturn’s Polar Configuration

Golden Age Alignment: Cochrane, alongside David Talbott, proposes Earth once orbited Saturn in a polar configuration, with Venus and Mars aligned axially. This "Saturnian System" allegedly produced the mythic "Primordial Sun" (Saturn) surrounded by Venus (rayed disc) and Mars (central "heart" or red disc)3,6. {Ev later found that it was Mars, not Saturn, that was the primordial sun-god.}

Plasma Mythology: Thunderbolts Project researchers (e.g., Wal Thornhill) posit that Birkeland currents—plasma filaments—connected Saturn, Venus, and Mars, visible as celestial "chains" or "dragons" in rock art. Venus’ retrograde rotation and slowed spin (noted in modern observations) may stem from these ancient electromagnetic interactions2,3.

Mythological Correlations

Global Warfare Myths: Conflicts like Inanna’s Descent (Sumer) and Osiris’ dismemberment (Egypt) allegorize plasma discharges between Venus and Mars, with Saturn as the "cosmic judge" or stabilizer3,7.

Velikovskian Echoes: Cochrane supports Immanuel Velikovsky’s claim that Venus’ retrograde rotation and Mars’ scarred surface resulted from recent (by geological standards) interplanetary chaos4.

Conclusion: Cochrane’s work synthesizes myth, petroglyphs, and plasma physics to argue that Venus, Mars, and Saturn once engaged in violent electromagnetic interactions, memorialized globally as divine battles and cometary imagery. These events challenge conventional Solar System timelines3,5,6.